Trafficking, Exploitation, Torture, Abusive Prison Conditions

Addis Ababa) – Ethiopians undertaking the perilous journey by boat across the Red Sea or Gulf of Aden face exploitation and torture in Yemen by a network of trafficking groups, Human Rights Watch said today. They also encounter abusive prison conditions in Saudi Arabia before being summarily forcibly deported back to Addis Ababa. Authorities in Ethiopia, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia have taken few if any measures to curb the violence migrants face, to put in place asylum procedures, or to check abuses perpetrated by their own security forces.

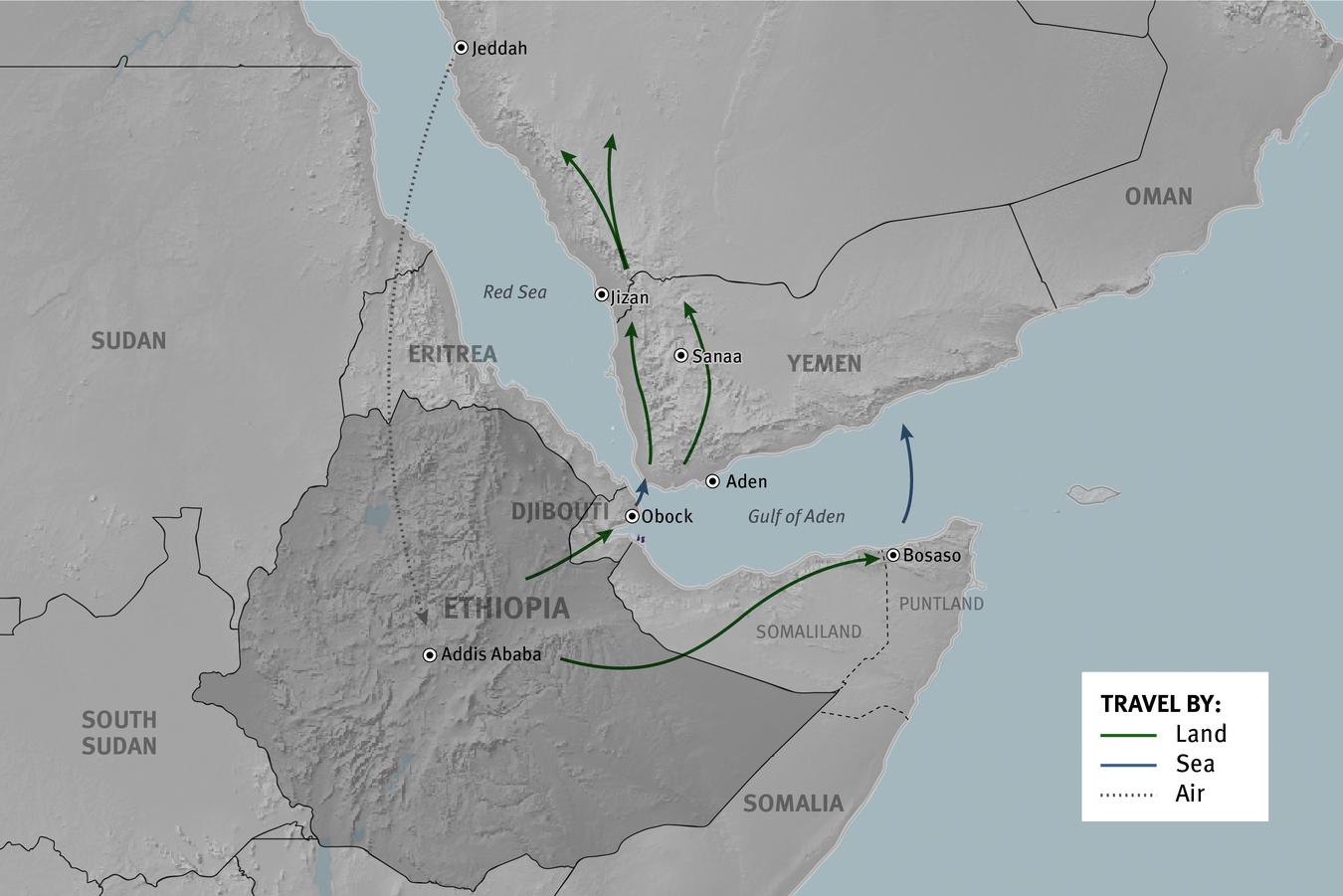

A combination of factors, including unemployment and other economic difficulties, drought, and human rights abuses have driven hundreds of thousands of Ethiopians to migrate over the past decade, traveling by boat over the Red Sea and then by land through Yemen to Saudi Arabia. Saudi Arabia and neighboring Gulf states are favored destinations because of the availability of employment. Most travel irregularly and do not have legal status once they reach Saudi Arabia.

“Many Ethiopians who hoped for a better life in Saudi Arabia face unspeakable dangers along the journey, including death at sea, torture, and all manners of abuses,” said Felix Horne, senior Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. “The Ethiopian government, with the support of its international partners, should support people who arrive back in Ethiopia with nothing but the clothes on their back and nowhere to turn for help.”

Human Rights Watch interviewed 12 Ethiopians in Addis Ababa who had been deported from Saudi Arabia between December 2018 and May 2019. Human Rights Watch also interviewed humanitarian workers and diplomats working on Ethiopia migration-related issues.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimates as many as 500,000 Ethiopians were in Saudi Arabia when the Saudi government began a deportation campaign in November 2017. The Saudi authorities have arrested, prosecuted, or deported foreigners who violate labor or residency laws or those who crossed the border irregularly. About 260,000 Ethiopians, an average of 10,000 per month, were deported from Saudi Arabia to Ethiopia between May 2017 and March 2019, according to the IOM, and deportations have continued.

An August 2 Twitter update by Saudi Arabia’s Interior Ministry said that police had arrested 3.6 million people, including 2.8 million for violations of residency rules, 557,000 for labor law violations, and 237,000 for border violations. In addition, authorities detained 61,125 people for crossing the border into Saudi Arabia illegally, 51 percent of them Ethiopians, and referred more than 895,000 people for deportation. Apart from illegal border crossing, these figures are not disaggregated by nationality.

Eleven of the 12 people interviewed who had been deported had engaged with smuggling and trafficking networks that are regionally linked across Ethiopia, Djibouti, Somalia’s semi-autonomous Puntland state, the self-declared autonomous state of Somaliland, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia. Traffickers outside of Ethiopia, particularly in Yemen, often used violence or threats to extort ransom money from migrants’ family members or contacts, those interviewed told Human Rights Watch. The 12th person was working in Saudi Arabia legally but was deported after trying to help his sister when she arrived illegally.

Those interviewed described life-threatening journeys as long as 24 hours across the Gulf of Aden or the Red Sea to reach Yemen, in most cases in overcrowded boats, with no food or water, and prevented from moving around by armed smugglers.

“There were 180 people on the boat, but 25 died,” one man said. “The boat was in trouble and the waves were hitting it. It was overloaded and about to sink so the dallalas [an adaptation of the Arabic word for “middleman” or “broker”] picked some out and threw them into the sea, around 25.”

Interviewees said they were met and captured by traffickers upon arrival in Yemen. Five said the traffickers physically assaulted them to extort payments from family members or contacts in Ethiopia or Somalia. While camps where migrants were held capture were run by Yemenis, Ethiopians often carried out the abuse. In many cases, relatives said they sold assets such as homes or land to obtain the ransom money.

After paying the traffickers or escaping, the migrants eventually made their way north to the Saudi-Yemen border, crossing in rural, mountainous areas. Interviewees said Saudi border guards fired at them, killing and injuring others crossing at the same time, and that they saw dead bodies along the crossing routes. Human Rights Watch has previously documented Saudi border guards shooting and killing migrants crossing the border.

“At the border there are many bodies rotting, decomposing,” a 26-year-old man said: “It is like a graveyard.”

Six interviewees said they were apprehended by Saudi border police, while five successfully crossed the border but were later arrested. They described abusive prison conditions in several facilities in southern Saudi Arabia, including inadequate food, toilet facilities, and medical care; lack of sanitation; overcrowding; and beatings by guards.

Planes returning people deported from Saudi Arabia typically arrive in Addis Ababa either at the domestic terminal or the cargo terminal of Bole International Airport. Several humanitarian groups conduct an initial screening to identify the most vulnerable cases, with the rest left to their own devices. Aid workers in Ethiopia said that deportees often arrive with no belongings and no money for food, transportation, or shelter. Upon arrival, they are offered little assistance to help them deal with injuries or psychological trauma, or to support transportation to their home communities, in some cases hundreds of kilometers from Addis Ababa.

Human Rights Watch learned that much of the migration funding from Ethiopia’s development partners is specifically earmarked to manage migration along the routes from the Horn of Africa to Europe and to assist Ethiopians being returned from Europe, with very little left to support returnees from Saudi Arabia.

“Saudi Arabia has summarily returned hundreds of thousands of Ethiopians to Addis Ababa who have little to show for their journey except debts and trauma,” Horne said. “Saudi Arabia should protect migrants on its territory and under its control from traffickers, ensure there is no collusion between its agents and these criminals, and provide them with the opportunity to legally challenge their detention and deportation.”

All interviews were conducted in Amharic, Tigrayan, or Afan Oromo with translation into English. The interviewees were from the four regions of SNNPR (Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region), Oromia, Amhara, and Tigray. These regions have historically produced the bulk of Ethiopians migrating abroad. To protect interviewees from possible reprisals, pseudonyms are being used in place of their real names. Human Rights Watch wrote to the Ethiopian and Saudi governments seeking comment on abuses described by Ethiopian migrants along the Gulf migration route, but at the time of writing neither had responded.

Dangerous Boat Journey

Most of the 11 people interviewed who entered Saudi Arabia without documents described life-threatening boat journeys across the Red Sea from Djibouti, Somaliland, or Puntland to Yemen. They described severely overcrowded boats, beatings, and inadequate food or water on journeys that ranged from 4 to 24 hours. These problems were compounded by dangerous weather conditions or encounters with Saudi/Emirati-led coalition naval vessels patrolling the Yemeni coast.

“Berhanu” said that Somali smugglers beat people on his boat crossing from Puntland: “They have a setup they use where they place people in spots by weight to keep the boat balanced. If you moved, they beat you.” He said that his trip was lengthened when smugglers were forced to turn the boat around after spotting a light from a naval vessel along the Yemeni coast and wait several hours for it to pass.

Since March 26, 2015, Saudi Arabia has led a coalition of countries in a military campaign against the Houthi armed group in Yemen. As part of its campaign the Saudi/Emirati-led coalition has imposed a naval blockade on Houthi-controlled Yemeni ports, purportedly to prevent Houthi rebels from importing weapons by sea, but which has also restricted the flow of food, fuel, and medicine to civilians in the country, and included attacks on civilians at sea. Human Rights Watch previously documented a helicopter attack in March 2017 by coalition forces on a boat carrying Somali migrants and refugees returning from Yemen, killing at least 32 of the 145 Somali migrants and refugees on board and one Yemeni civilian.

Exploitation and Abuses in Yemen

Once in war-torn Yemen, Ethiopian migrants said they faced kidnappings, beatings, and other abuses by traffickers trying to extort ransom money from them or their family members back home.

This is not new. Human Rights Watch, in a 2014 report, documented abuses, including torture, of migrants in detention camps in Yemen run by traffickers attempting to extort payments. In 2018, Human Rights Watch documented how Yemeni guards tortured and raped Ethiopian and other Horn of Africa migrants at a detention center in Aden and worked in collaboration with smugglers to send them back to their countries of origin. Recent interviews by Human Rights Watch indicate that the war in Yemen has not significantly affected the abuses against Ethiopians migrating through Yemen to Saudi Arabia. If anything, the conflict, which escalated in 2015, has made the journey more dangerous for migrants who cross into an area of active fighting.

Seven of the 11 irregular migrants interviewed said they faced detention and extortion by traffickers in Yemen. This occurred in many cases as soon as they reached shore, as smugglers on boats coordinated with the Yemeni traffickers. Migrants said that Yemeni smuggling and trafficking groups always included Ethiopians, often one from each of Oromo, Tigrayan, and Amhara ethnic groups, who generally were responsible for beating and torturing migrants to extort payments. Migrants were generally held in camps for days or weeks until they could provide ransom money, or escape. Ransom payments were usually made by bank transfers from relatives and contacts back in Ethiopia.

“Abebe” described his experience:

When we landed… [the traffickers] took us to a place off the road with a tent. Everyone there was armed with guns and they threw us around like garbage. The traffickers were one Yemeni and three Ethiopians – one Tigrayan, one Amhara, and one Oromo…. They started to beat us after we refused to pay, then we had to call our families…. My sister [in Ethiopia] has a house, and the traffickers called her, and they fired a bullet near me that she could hear. They sold the house and sent the money [40,000 Birr, US $1,396].

“Tesfalem”, said that he was beaten by Yemenis and Ethiopians at a camp he believes was near the port city of Aden:

They demanded money, but I said I don’t have any. They told me to make a call, but I said I don’t have relatives. They beat me and hung me on the wall by one hand while standing on a chair, then they kicked the chair away and I was swinging by my arm. They beat me on my head with a stick and it was swollen and bled.

He escaped after three months, was detained in another camp for three months more, and finally escaped again.

“Biniam” said the men would take turns beating the captured migrants: “The [Ethiopian] who speaks your language beats you, those doing the beating were all Ethiopians. We didn’t think of fighting back against them because we were so tired, and they would kill you if you tried.”

Two people said that when they landed, the traffickers offered them the opportunity to pay immediately to travel by car to the Saudi border, thereby avoiding the detention camps. One of them, “Getachew,” said that he paid 1,500 Birr (US $52) for the car and escaped mistreatment.

Others avoided capture when they landed, but then faced the difficult 500 kilometer journey on foot with few resources while trying to avoid capture.

Dangers faced by Yemeni migrants traveling north were compounded for those who ran into areas of active fighting between Houthi forces and groups aligned with the Saudi/Emirati-led coalition. Two migrants said that their journey was delayed, one by a week, the other by two months, to avoid conflict areas.

Migrants had no recourse to local authorities and did not report abuses or seek assistance from them. Forces aligned with the Yemeni government and the Houthis have also detained migrants in poor conditions, refused access to protection and asylum procedures, deported migrants en masse in dangerous conditions, and exposed them to abuse. In April 2018, Human Rights Watch reported that Yemeni government officials had tortured, raped, and executed migrants and asylum seekers from the Horn of Africa in a detention center in the southern port city of Aden. The detention center was later shut down.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) announced in May that it had initiated a program of voluntary humanitarian returns for irregular Ethiopian migrants held by Yemeni authorities at detention sites in southern Yemen. IOM said that about 5,000 migrants at three sites were held in “unsustainable conditions,” and that the flights from Aden to Ethiopia had stalled because the Saudi/Emirati-led coalition had failed to provide the flights the necessary clearances. The coalition controls Yemen’s airspace.

Crossing the Border; Abusive Detention inside Saudi Arabia

Migrants faced new challenges attempting to cross the Saudi-Yemen border. The people interviewed said that the crossing points used by smugglers are in rural, mountainous areas where the border separates Yemen’s Saada Governorate and Saudi Arabia’s Jizan Province. Two said that smugglers separated Ethiopians by their ethnic group and assigned different groups to cross at different border points.

Ethiopian migrants interviewed were not all able to identify the locations where they crossed. Most indicated points near the Yemeni mountain villages Souq al-Ragu and ‘Izlat Al Thabit, which they called Ragu and Al Thabit. Saudi-aligned media have regularly characterized Souq al-Ragu as a dangerous townfrom which drug smugglers and irregular migrants cross into Saudi Arabia.

Migrants recounted pressures to pay for the crossing by smuggling drugs into Saudi Arabia. “Abdi” said he stayed in Souq al-Ragu for 15 days and finally agreed to carry across a 25 kilogram sack of khat in exchange for 500 Saudi Riyals (US$133). Khat is a mild stimulant grown in the Ethiopian highlands and Yemen; it is popular among Yemenis and Saudis, but illegal in Saudi Arabia.

“Badessa” described Souq al-Ragu as “the crime city:”

You don’t know who is a trafficker, who is a drug person, but everybody has an angle of some sort. Even Yemenis are afraid of the place, it is run by Ethiopians. It is also a burial place; bodies are gathered of people who had been shot along the border and then they’re buried there. There is no police presence.

Four of the eleven migrants who crossed the border on foot said Saudi border guards shot at them during their crossings, sometimes after ordering them to stop and other times without warning. Some said they encountered dead bodies along the way. Six said they were apprehended by Saudi border guards or drug police at the border, while five were arrested later.

“Abebe” said that Saudi border guards shot at his group as they crossed from Izlat Al Thabit:

They fired bullets, and everyone scattered. People fleeing were shot, my friend was shot in the leg…. One person was shot in the chest and killed and [the Saudi border guards] made us carry him to a place where there was a big excavator. They didn’t let us bury him; the excavator dug a hole and they buried him.

Berhanu described the scene in the border area: “There were many dead people at the border. You could walk on the corpses. No one comes to bury them.”

Getachew added: “It is like a graveyard. There are no dogs or hyenas there to eat the bodies, just dead bodies everywhere.”

Two of the five interviewees who crossed the border without being detained said that Saudi and Ethiopian smugglers and traffickers took them to informal detention camps in southern Saudi towns and held them for ransom. “Yonas” said they took him and 14 others to a camp in the Fayfa area of Jizan Province: “They beat me daily until I called my family. They wanted 10,000 Birr ($349). My father sold his farmland and sent the 10,000 Birr, but then they told me this isn’t enough, we need 20,000 ($698). I had nothing left and decided to escape or die.” He escaped.

Following their capture, the migrants described abusive conditions in Saudi governmental detention centers and prisons, including overcrowding and inadequate food, water, and medical care. Migrants also described beatings by Saudi guards.

Nine migrants who were captured while crossing the border illegally or living in Saudi Arabia without documentation spent up to five months in detention before authorities deported them back to Ethiopia. The three others were convicted of criminal offenses that included human trafficking and drug smuggling, resulting in longer periods in detention before being deported.

The migrants identified about 10 prisons and detention centers where they were held for various periods. The most frequently cited were a center near the town of al-Dayer in Jizan Province along the border, Jizan Central Prison in Jizan city, and the Shmeisi Detention Center east of Jeddah, where migrants are processed for deportation.

Al-Dayer had the worst conditions, they said, citing overcrowding, inadequate sanitation, food and water, and medical care. Yonas said:

They tied our feet with chains and they beat us while chained, sometimes you can’t get to the food because you are chained. If you get chained by the toilet it will overflow and flow under you. If you are aggressive you get chained by the toilet. If you are good [behave well], they chain you to another person and you can move around.

Abraham had a similar description:

The people there beat us. Ethnic groups [from Ethiopia] fought with each other. The toilet was overflowing. It was like a graveyard and not a place to live. Urine was everywhere and people were defecating. The smell was terrible.

Other migrants described similarly bad conditions in Jizan Central Prison. “Ibrahim” said that he was a legal migrant working in Saudi Arabia, but that he travelled to Jizan to help his sister, whom Saudi authorities had detained after she crossed from Yemen illegally. Once in Jizan, authorities suspected him of human trafficking and arrested him, put him on trial, and sentenced him to two years in prison, a sentenced he partially served in Jizan Central Prison:

Jizan prison is so very tough…. You can be sleeping with [beside] someone who has tuberculosis, and if you ask an official to move you, they don’t care. They will beat you. You can’t change clothes, you have one set and that is it, sometimes the guards will illegally bring clothes and sell to you at night.

He also complained of overcrowding: “When you want to sleep you tell people and they all jostle to make some room, then you sleep for a bit but you wake up because everyone is jostling against each other.”

Most of the migrants said food was inadequate. Yonas described the situation in al-Dayer: “When they gave food 10 people would gather and fight over it. If you don’t have energy you won’t eat. The fight is over rice and bread.”

Detainees also said medical care was inadequate and that detainees with symptoms of tuberculosis (such as cough, fever, night sweats, or weight loss) were not isolated from other prisoners. Human Rights Watch interviewed three former detainees who were being treated for tuberculosis after being deported, two of whom said they were held with other detainees despite having symptoms of active tuberculosis.

Detainees described being beaten by Saudi prison guards when they requested medical care. Abdi said:

I was beaten once with a stick in Jizan that was like a piece of rebar covered in plastic. I was sick in prison and I used to vomit. They said, ‘why do you do that when people are eating?’ and then they beat me harshly and I told him [the guard], ‘Please kill me.’ He eventually stopped.

Ibrahim said he was also beaten when he requested medical care for tuberculosis:

[Prison guards] have a rule that you aren’t supposed to knock on the door [and disturb the guards]. When I got sick in the first six months and asked to go to the clinic, they just beat me with electric wires on the bottom of my feet. I kept asking so they kept beating.

Detainees said that the other primary impetus for beatings by guards was fighting between different ethnic groups of Ethiopians in detention, largely between ethnic Oromos, Amharas, and Tigrayans. Ethnic tensions are increasingly common back in Ethiopia.

Detainees said that conditions generally improved once they were transferred to Shmeisi Detention Center, near Jeddah, where they stayed only a few days before receiving temporary travel documents from Ethiopian consular authorities and deported to Ethiopia. The migrants charged with and convicted of crimes had no opportunity to consult legal counsel.

None of the migrants said they were given the opportunity to legally challenge their deportations, and Saudi Arabia has not established an asylum system under which migrants could apply for protection from deportation where there was a risk of persecution if they were sent back. Saudi Arabia is not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention.

Deportation and Future Prospects

Humanitarian workers and diplomats told Human Rights Watch that since the beginning of Saudi Arabia’s deportation campaign, large numbers of Ethiopian deportees have been transported via special flights by Saudia Airlines to Bole International Airport in Addis Ababa and unloaded in a cargo area away from the main international terminal or at the domestic terminal. When Human Rights Watch visited in May, it appeared that the Saudi flights were suspended during the month of Ramadan, during which strict sunrise-to-sunset fasting is observed by Muslims. All interviewees who were deported in May said they had returned on regular Ethiopian Airlines commercial flights and disembarked at the main terminal with other passengers.

All of those deported said that they returned to Ethiopia with nothing but the clothes they were wearing, and that Saudi authorities had confiscated their mobile phones and in some cases shoes and belts. “After staying in Jeddah … they had us make a line and take off our shoes,” Abraham said. “Anything that could tie like a belt we had to leave, they wouldn’t let us take it. We were barefoot when we went to the airport.”

Deportees often have critical needs for assistance, including medical care, some for gunshot wounds. One returnee recovering from tuberculosis said that he did not have enough money to buy food and was going hungry. Abdi said that when he left for Saudi Arabia he weighed 64 kilograms but returned weighing only 47 or 48 kilograms.

Aid workers and diplomats familiar with migration issues in Ethiopia said that very little international assistance is earmarked for helping deportees from Saudi Arabia for medical care and shelter or money to return and reintegrate in their home villages.

Over 8 million people are in need of food assistance in Ethiopia, a country of over 100 million. It hosts over 920,000 refugees from neighboring countries and violence along ethnic lines produced over 2.4 internally displaced people in 2018, many of whom have now been returned.

The IOM registers migrants upon arrival in Ethiopia and to facilitate their return from Saudi Arabia. Several hours after their arrival and once registered, they leave the airport and must fend for themselves. Some said they had never been to Addis before.

In 2013 and 2014, Saudi Arabia conducted an expulsion campaign similar to the one that began in November 2017. The earlier campaign expelled about 163,000 Ethiopians, according to the IOM. A 2015 Human Rights Watch report found that migrants experienced serious abuses during detention and deportation, including attacks by security forces and private citizens in Saudi Arabia, and inadequate and abusive detention conditions. Human Rights Watch has also previously documented mistreatment of Ethiopian migrants by traffickers and government detention centers in Yemen.

Aid workers and diplomats said that inadequate funding to assist returning migrants is as a result of several factors, including a focus of many of the European funders on stemming migration to and facilitating returns from Europe, along with competing priorities and the low visibility of the issue compared with migration to Europe.

During previous mass returns from Saudi Arabia, there was more funding for reintegration and more international media attention in part because there was such a large influx in a short time, aid workers said.